Ancient ‘Lost City’ in Atlantic Depths Reveals Clues to Life’s Origins

Deep in the Atlantic Ocean lies the Lost City Hydrothermal Field, a ghostly landscape of towering mineral spires that may hold secrets to life’s origins. Discovered over 2,300 feet below the surface on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, this 120,000-year-old vent system is Earth’s oldest known underwater hydrothermal environment. Unlike volcanic vents, it thrives on chemical reactions between seawater and mantle rock—a process called serpentinization. These reactions produce methane and hydrogen, fueling microbial life without sunlight or oxygen, akin to conditions on early Earth.

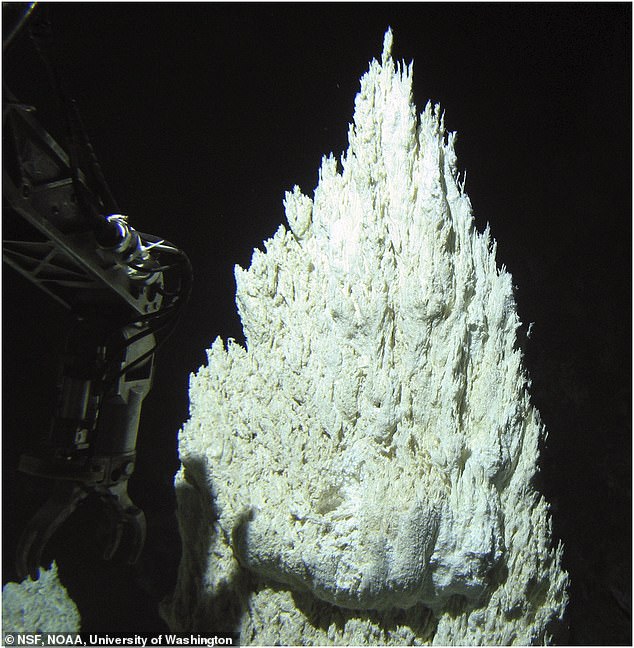

[Image: Spire formations at the Lost City Hydrothermal Field, with towering carbonate chimneys stretching toward the water’s surface.]

Caption: The Lost City’s spires result from mineral-rich fluids reacting with seawater, forming structures up to 200 feet tall.

A Window to Early Earth

The site’s alkaline vents, like “IMAX” and “Poseidon,” release warm fluids rich in hydrocarbons—organic compounds critical for life. Scientists recently extracted a core sample of mantle rock from the field, revealing how subsurface reactions generate these molecules. This process mirrors conditions billions of years ago, when life may have emerged from similar chemistry. Microbes here thrive in darkness, using methane and hydrogen as energy sources. Larger creatures, such as shrimp and snails, cling to the spires, but the ecosystem remains sparse due to limited nutrients.

[Image: Map highlighting the Lost City’s location near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, southwest of the Azores.]

Caption: Isolated and untouched, the Lost City lies 9 miles west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, far from human activity.

A Blueprint for Alien Life?

The Lost City’s extremes offer clues about life beyond Earth. “This ecosystem could exist on moons like Enceladus or Europa,” says microbiologist William Brazelton. These icy worlds, with subsurface oceans, might host similar vents where life could emerge. The field’s longevity—some spires are 60 meters tall after millennia—acts as a natural lab, showcasing how organic molecules form without sunlight.

[Image: Close-up of microbial communities thriving in a vent chimney.]

Caption: Microbes in the chimneys survive on chemical energy, offering insights into primordial life.

Threats and Conservation

Despite its scientific value, the Lost City faces risks. In 2017, Poland secured exploration rights nearby for deep-sea mining. While the field itself lacks minerals, adjacent areas contain valuable metals. Mining could release toxic plumes, endangering the fragile ecosystem. Though designated an Ecologically Significant Marine Area (EBSA), this status lacks legal power. UNESCO is evaluating the site for World Heritage protection, which could shield it from exploitation.

[Image: Illustration of deep-sea mining equipment near hydrothermal vents.]

Caption: Mining operations near the Lost City could disrupt its delicate chemical and biological balance.

Scientists warn that damaging this ancient system could erase irreplaceable clues about life’s beginnings—and our search for life elsewhere. Preserving the Lost City isn’t just about protecting the ocean’s past; it’s about safeguarding a key to understanding our cosmic future.

Word count: ~600