Reconstructing Ancient Egypt’s Lost Female Pharaoh: Queen Hatshepsut’s Resurrected Visage

Hatshepsut: Egypt’s Overlooked Female Pharaoh and the Truth Behind Her Defaced Statues

Among ancient Egypt’s rulers, Queen Hatshepsut remains one of history’s most intriguing yet underappreciated figures. As one of the few women to seize the title of pharaoh, she co-ruled Egypt for over two decades (c. 1479–1458 BC), overseeing an era of peace, prosperity, and artistic innovation. Despite her achievements, her legacy was nearly erased—her statues destroyed, and her name omitted from later historical records. For centuries, scholars assumed this was driven by personal animosity from her stepson and successor, Thutmose III. New research, however, suggests a more practical explanation.

From Queen to Pharaoh

Hatshepsut began her reign as regent for Thutmose III, her young stepson, after the death of her husband (and half-brother), Thutmose II. In a bold move, she declared herself pharaoh, adopting male titles, garments, and even the ceremonial false beard. Her rule saw landmark achievements, including ambitious construction projects like her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri and lucrative trade expeditions to the Land of Punt. Yet, following her death, many of her monuments were defaced or repurposed, sparking theories of a vengeful campaign by Thutmose III.

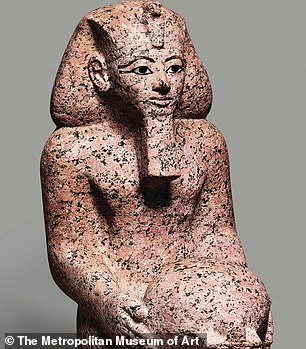

[Image: Statue of Hatshepsut at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, depicting her in traditional pharaonic regalia, including the false beard.]

Rethinking the Destruction

Dr. Jun Yi Wong, an Egyptologist at the University of Toronto, challenges the traditional narrative. His study, published in Antiquity, reveals that many statues attributed to Hatshepsut were strategically broken at their weakest points—necks, waists, and knees—suggesting systematic disassembly rather than violent destruction. Fragments were often reused as building materials or tools, a common practice called “ritual deactivation” to neutralize a former ruler’s spiritual presence. Notably, numerous statues survived intact, their faces untouched, contradicting the idea of widespread hostility.

[Image: Fragments of a limestone statue of Hatshepsut, excavated in the 1920s, showing methodical breakage patterns.]

A Nuanced Legacy

While Thutmose III did remove Hatshepsut’s name from monuments decades after her death, Dr. Wong argues this was likely a political move to reinforce his lineage, not personal spite. “Her treatment aligns with how male pharaohs were handled,” he explains, emphasizing that reuse of materials was pragmatic in resource-scarce Egypt. Still, Hatshepsut’s gender made her vulnerable to erasure. Unlike male rulers, her unprecedented role as a female king may have unsettled traditional power structures, prompting later generations to downplay her reign.

Rediscovery and Recognition

Hatshepsut’s remains, found in the Valley of the Kings in 1930, were conclusively identified in 2007 via DNA and dental analysis. Modern archaeology has since restored her place in history, celebrating her as a master strategist and innovator. Today, her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri—a marvel of ancient architecture—stands as a testament to her vision, overshadowing neighboring monuments.

[Image: Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, a terraced structure blending seamlessly with limestone cliffs.]

Conclusion

Hatshepsut’s story reflects both the heights of ancient Egyptian achievement and the fragility of historical memory. Once dismissed as a footnote, she is now recognized as a trailblazer who defied gender norms to lead her kingdom into a golden age. The fractured statues, once seen as symbols of resentment, now reveal a deeper truth: her reign was not hated but pragmatically recycled, much like the pharaohs before her. In death, Hatshepsut finally emerges not as a target of vengeance, but as a ruler whose legacy proved too enduring to erase completely.

Who Was Hatshepsut?

- Reign: c. 1479–1458 BC (18th Dynasty).

- Achievements: Expanded trade, commissioned iconic monuments, stabilized Egypt’s economy.

- Legacy: Among Egypt’s most successful rulers, male or female, yet omitted from king lists for centuries.

[Word count: ~600]